Dacia (Roman province)

| History of Romania | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Prehistory | |

| Dacia | |

| Dacian Wars | |

| Roman Dacia | |

| Thraco-Roman syncretism | |

| Early Middle Ages | |

| Origin of the Romanians | |

| Middle Ages | |

| History of Transylvania | |

| Foundation of Wallachia | |

| Foundation of Moldavia | |

| Early Modern Times | |

| Principality of Transylvania | |

| Phanariotes | |

| Danubian Principalities | |

| National awakening | |

| Organic Statute | |

| 1848 Moldavian Revolution | |

| 1848 Wallachian Revolution | |

| United Principalities | |

| War of Independence | |

| Kingdom of Romania | |

| World War I | |

| Union with Transylvania | |

| Union with Bessarabia | |

| Greater Romania | |

| Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina | |

| World War II | |

| Communist Romania | |

| Soviet occupation | |

| 1989 Revolution | |

| Romania since 1989 | |

| Topic | |

| Timeline | |

| Military history | |

|

Romania Portal |

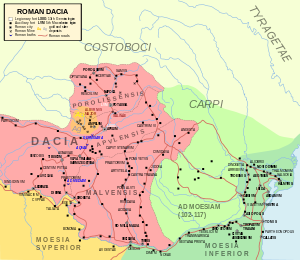

Roman Dacia[1], also Dacia Traiana[2] or Dacia Felix[3], was a province of the Roman Empire (106-271/275 AD).[1][2][4] Its territory consisted of eastern and southeastern Transylvania, the Banat, and Oltenia (regions of modern Romania).[3] Dacia was from the very beginning organized as an imperial province and remained so throughout the Roman occupation.[5] Historians’ estimates of the population of Roman Dacia range from 650,000 to 1,200,000.[6]

The conquest of Dacia was completed by Emperor Trajan (98-117) after two major campaigns against Decebalus’s Dacian kingdom.[3] But the territory of the Dacian kingdom was not occupied in its entirety by the Romans;[5] the greater part of Moldavia, together with Maramureş and Crişana, was ruled by Free Dacians even after the Roman conquest.[6]

In 119, the province was divided into two departments: Upper Dacia included the Transylvanian Plateau;[2] and Lower Dacia incorporated the Banat and almost half of Oltenia;[3][5][6] the latter was later named Dacia Malvensis.[2] In 124 (or around 158), Upper Dacia was divided into two provinces: Dacia Apulensis and Dacia Porolissensis (north-western Transylvania).[5][7] During (or soon after) the Marcomannic Wars this scheme was modified again: military and judicial administration was unified under the command of one governor having two other senators (the legati legionis) as his subordinates and the province was called simply Dacia or Three Dacias (tres Daciæ).[5]

The Roman authorities unfolded in Dacia a massive and organized colonization.[4] New mines were opened, and ore extraction intensified.[3] Agriculture, stockbreeding, and commerce flourished in the province.[3] Dacia began to supply grains not only to the military personnel stationed in the province but also to the rest of the Balkan area.[3]

Dacia was a highly urban province: no fewer than 11[1] or 12 cities are known, 8 of them of the highest rank (colonia);[6] but the number of cities was fewer than in the region’s other provinces.[8] In Dacia, all the cities developed from military camps.[1] Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa (Sarmizegetusa, Romania), the seat of the imperial procurator (finance officer) for all the three subdivisions, was the financial, religious, and legislative center of the province.[1] Apulum (Alba Iulia, Romania), where the military governor of the three subdivisions had his headquarters,[1] was not just the greatest conurbation of the province, but one of the largest in the area.[5]

The province’s political life was not without perils from the start.[6] First came the Free Dacians who, allied with the Sarmatians, frequently attacked the province.[6] After the quieter rules of Commodus (180-193), Septimius Severus (193-211), and Caracalla (211-217), the invasions of Dacia, in particular the invasion by the Carpi (a Dacian tribe) in alliance with the Goths, were a serious problem for the emperors.[6]

It became more and more difficult to keep Dacia within the boundaries of the Roman Empire;[4] thus Dacia was the last province to be added to the Roman Empire and was the first to be abandoned.[3] In the 250s, as the Carpi advance intensified, Dacia’s inhabitants began to seek refuge south of the river Danube, in Moesia.[8] Our sources from antiquity imply that Dacia had already been lost during the reign of Gallienus (260-268), but they also report that it was Aurelian (270-275) who relinquished Dacia Traiana.[9] He evacuated his troops and civilian administration from Dacia, and founded Dacia Aureliana with its capital at Serdica (Sofia, Bulgaria) in Lower Moesia.[2]

The fate of the Romanized population of the former province of Dacia Traiana has become subject to a spirited controversy.[6] One theory holds that the Latin language spoken in ancient Dacia, where Romania was to be formed in the future, gradually turned into Romanian; in parallel, a new people, the Romanians were formed from the Daco-Romans (the Romanized population of Dacia Traiana).[4] The opposing theory argues that the Romanians descended from the Romanized population of the Roman provinces of the Balkan Peninsula.[8]

Trajan conquered the Dacians, under King Decibalus, and made Dacia, across the Danube in the soil of barbary, a province which in circumference had ten times 100,000 paces; but it was lost under Imperator Gallienus, and, after Romans had been transferred from there by Aurelian, two Dacias were made in the regions of Moesia and Dardania.—Festus: Breviarium of the Accomplishments of the Roman People (VII.2)[10]

Contents |

Background: the Dacian kingdom and the Roman Empire

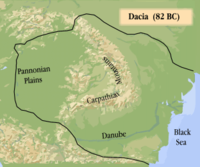

The Dacians and the Getae were in constant and frequent interaction with the Romans throughout the late pre-Roman period.[5] The interest in the presence of the native tribes on the lower Danube reaches a significant point when Burebista[5] (82-44 BC)[4] established a powerful polity, extending his authority over a large area, as far as Pannonia in the west and the Greek cities on the Black Sea to the south and the east.[6]

By 74 BC,[6] the Roman legions reached the lower Danube after a rapid succession of victories against many Dacian tribes settled on its banks.[2] Burebista was perceived as a powerful dynast at the borders of the empire, important enough to play a role not just within the boundaries of his kingdom but also in the political games of Rome (for example, his last-hour ally of Pompey before the battle of Pharsalus).[5] Julius Caesar planned an expedition against the Parthians and en route hoped to cut short the political development of the Dacians under Burebista.[11] Failing to implement the idea of unity in the political mentality of the multi-ethnic society he ruled, this lead to the death of Burebista (possibly as a result of a political plot against him); after his death his dominion broke into four, and later into five parts under different reguli (minor kings).[5]

The period between Burebista’s death and the accession of Decebalus was marked by much fighting between Dacians and Romans.[5] Both the Dacians and the Getae were still perceived as a threat by the Roman Empire, and because of their frequent raiding expeditions into Roman territories, provincial or central leaders planned and undertook reprisals against them.[5] On the other hand, it is clear that the Dacians and the Getae were in constant and frequent interaction with the Romans throughout the late Roman period.[5] Often they were diplomatic partners and played active parts in the political games of Rome, often as amicii et socii (“friends and partners”), possibly of Rome herself but usually of individual Roman leaders.[5] For example, in his fight against Mark Antony, Octavian sought to ally himself with the Dacians: in 35 BC, he asked for the hand of King Cotiso’s daughter in exchange for the king’s betrothal to Octavian’s daughter Julia.[2]

The handing of hostages to the Romans (usually members of kings’ families) might have started as early as 71 BC and continued later under Octavianus Augustus and throughout the 1st century AD.[5] In turn the presence in Dacia of individuals from the Roman Empire as merchants, craftsmen and runaways (slaves or freemen) has been accepted by literary sources.[5] The economic relations induced multiple influences through active exchange of goods and technologies, especially in the area of Orăştie Mountains.[5]

The Flavian dynasty, particularly Domitian (81-96), engaged Roman troops along the lower and middle Danube in what amounted to an opening skirmish against the Dacians.[11] But real hostilities did not begin in earnest until Trajan attacked the Dacians with the full weight of Roman might.[11] The Roman armies under Trajan's command crossed the Danube into the Dacian territory targeting directly the core are in the Orăştie Mountains.[5] In 102[4], after a series of encounters, a peace agreement was reached: Decebalus was to destroy his fortresses and a Roman garrison was installed at Sarmizegetusa Regia (Grădiştea Muncelului, Romania) to watch over the agreement.[5] Trajan also ordered his engineer, Apollodorus of Damascus[1] to design and build a bridge across the Danube at Drobeta (Drobeta-Turnu Severin, Romania).[4]

Trajan’s second Dacian campaign in 105-106 was very specific in its aim of expansion and conquest.[5] The offensive was aimed directly at Sarmizegetusa Regia.[12] The Romans besieged Decebalus’s capital which surrendered to them and was destroyed.[4] The Dacian king and a handful of his faithful followers withdrew into the mountains, but their resistance was short-lived and Decebalus committed suicide.[4] Other Dacian nobles, however, were captured or decided to surrender.[12] One of the latter revealed the whereabouts of the Dacian royal treasury which proved to be of stupendous value: 500,000 pounds (226,800 kilograms) of gold and 1,000,000 pounds (453,600 kilograms) of silver.[12]

It is an excellent idea of yours to write about the Dacian war. There is no subject which offers such scope and such a wealth of original material, no subject so poetic and almost legendary although its facts are true. You will describe new rivers set flowing over the land, new bridges built across rivers, and camps clinging to sheer precipices; you will tell of a king driven from his capital and finally to death, but courageous to the end; you will record a double triumph one the first over a nation hitherto unconquered, the other a final victory.—Pliny the Younger: Letters (Book VIII, Letter 4: To Caninius Rufus)[13]

Dacia under the Antonian and Severan emperors (106-235)

Establishment (106-117)

Decebalus’s kingdom was now annexed: Dacia was to be a new Roman province, the first such acquisition for more than a half century.[14] There remained only the mopping-up of Decebalus’ northern Sarmatian allies, a series of operations which continued until at least 107;[12] but by the end of 106, with victory won, Roman units had been busily erecting new forts around the frontiers.[14] Trajan returned to Rome in the middle of June 107.[12]

Roman sources first include Dacia among the imperial provinces on August 11, 106.[6] Dacia was under the command of a governor with the rank of former consul backed up by two legati legionis, while all the finances (taxation and payments to the military) were handled by a financial procurator.[5] The occupation took different forms for different parts of the Dacian territory: Eastern Oltenia, Muntenia and South Moldavia were added to the territory of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior);[5] Dacia Traiana included only the Banat, the middle corridor of Transylvania, and the western half of Oltenia.[2]

To the south and the east of the new province’s borders was the Roman province of Moesia, which in the year 86 had been divided by Emperor Domitian into Upper Moesia (Moesia Superior) with its capital Singidunum (Belgrade, Serbia) and Lower Moesia, with its capital at Tomis (Constanţa, Romania).[3] Along Dacia’s western border, Iazyges (a Sarmatian tribe) inhabited the Pannonian Plain; the northern part of Transylvania was inhabited by Free Dacians and Costoboci (another Dacian tribe), while northern Moldavia was inhabited by Carpi, Roxolani, and Bastarns.[3]

Provincialization required a great commitment of resources, usually including colonies of veterans, new road systems, and the building of urban amenities that were the hallmarks of Roman civilization.[11] But, except for Trajan’s efforts to recruit settlers for Dacia, the government did very little to encourage civilians moving into newly conquered areas.[11]

The wars ended not only in the destruction of Dacia’s military might but also in a sudden drop in its population.[8] Crito reported that some 500,000 Dacians were taken prisoner, many to be sent to Rome to figure in the gladiatorial exhibitions (lusiones) that would form part of Trajan’s triumph, while the systematic ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the conquered territory began.[12] The empire followed an organized, official colonization policy, granting land even to those who were not Roman citizens.[6]

The province’s new capital, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, was placed at a distance of 40 kilometers (24 miles) southwest from the original Sarmizegetusa Regia, now laid to waste.[2] Initially, it served as a command post for the Legio XIII Gemina.[2] Those who were settled there included veterans of the Dacian Wars from the legions XIV Gemina, V Macedonica, and XI Claudia.[8]

The Roman strongholds were connected with a network of military roads that began at Apollodorus’s bridge and stretched into Banat and Transylvania.[2] According to the epigraph on a milestone, the road between Potaissa (Turda, Romania) and Napoca (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) was completed by 109–110 A.D.[8]

The first re-organizations (117-138)

Hadrian was in Syria when he was informed of Trajan’s death.[14] But he could not yet return to Rome, because he was also informed that Quadratus Bassus, sent by Trajan to defend the new territories beyond the Danube, had died on a campaign in Dacia.[14] The garrison of Dacia and the Danubian provinces was below strength: several legions and numerous auxiliary regiments had been drawn off for Trajan’s Parthian expedition.[14] The frustrated Iazyges, who had helped the Romans conquer Dacia, decided to revolt again and take back their portion of the promised Dacian land; and they were also supported by the Roxolani.[2] Hence Hadrian sent ahead the armies from the east, and he would follow as soon as he could safely leave Syria.[14]

The emperor was so unhappy with the festering problems north of the Danube that at one point he considered evacuating Dacia.[2] The order was even given to dismantle the superstructure of the Danube bridge below the Iron Gates.[14] Probably it was only an emergency measure, taken because an enemy breakthrough westwards across the Olt River or southwards from a point between the legionary base Bersobis and Trajan’s Dacian colonia, was a real threat.[14]

Large portions of Trajan’s conquest north of the Lower Danube were abandoned: the great plains of Oltenia and Muntenia, the southeastern flanks of the Carpathians and southern Moldavia, which had all been added to Lower Moesia, were restored to the Roxolani.[14] Consequently, Lower Moesia returned to its original boundaries from before the conquest of the Dacian territories.[5] The remaining part of Lower Moesia north of the Danube now became a separate province and was labeled Lower Dacia (Dacia Inferior).[14] Trajan’s Dacia received the name Upper Dacia (Dacia Superior).[14] By that time, Hadrian had transferred the Legio IV Flavia Felix from Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa back to Upper Moesia.[2]

By 124, another new province was carved out in the northern part of Upper Dacia, and named Dacia Porolissensis[8]; its territory corresponded to north-western Transylvania.[5] Since, according to the prescriptions of Roman administration, former consuls could only rule provinces with more than one legion, Upper Dacia was in subsequent decades administered by officials of the next lower rank, i.e. senators, who became consuls only at the end of their terms as governor;[8] the governor of Upper Dacia was also the commander of the only legion left at Apulum.[5] Lower Dacia and Dacia Porolissensis were under the command of praesidial procurators of ducenary rank.[5]

Hadrian paid particular attention to the mining industry;[2] the mines became a monopoly of the Roman emperors, who administered them, under lease, through a vast bureaucracy of overseers, sub-overseers, registrars, bookkeepers, paymasters, and file-clerks.[1] In 124, the emperor visited Napoca and made the city a municipium.[1]

Consolidation (138-161)

Antoninus Pius consolidated the northern and eastern borders of Dacia that faced the barbarian world.[2] The unusual number of milestones from this reign shows that he was especially interested in keeping the roads in repair.[1] Stamped tiles show that the amphitheater at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, which had been built during the earliest years of the colonia, was repaired under his rule.[1] The larger of the camps at exposed Porolissum (near Moigrad, Romania) was rebuilt in stone and strongly walled.[7]

Antoninus Pius re-divided the civilian and military administration of this important province into Dacia Porolissensis (northern Transylvania) with its capital at Porolissum, Dacia Apulensis (mainly the Banat) with its capital at Apulum, and Dacia Malvensis (currently Oltenia) with its capital at Romula (Reşca Dobrosloveni, Romania).[2] All were ruled by military prefects under the same governor.[2]

Markommanic Wars and their effects (161-193)

In 166-167, the barbarians (the Quadi and Marcomanni)[7] began to pour across the river Danube into Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, and through Dacia into Moesia.[15] Apparently, war reached northern Dacia after 167[1] – the Iazyges, having been thwarted in Pannonia, turned their attention to Dacia and seized the valuable gold mines at Alburnus Maior (Roşia Montană, Romania).[15] The last date found on the wax tablets discovered in the mineshafts there (which had been hidden when an enemy attack seemed imminent) is 29 May 167.[8] The suburban villas at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa were burned; and the camp at Slăveni was also destroyed by the Marcomanni.[1]

Dacia, being exposed to attack on three sides, was particularly difficult to defend; and since Dacia could not halt all the attacks, Upper and Lower Moesia also came under heavy pressure from the barbarians.[8] In 168, to eliminate delay and confusion in the chain of command, Marcus Aurelius united the three provinces in Dacia into a single military province with its capital in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.[2] In 170, Dacia was invaded by Chauci who first defeated the free Costoboci and then destroyed many Roman castri, among them the fortress of Tibiscum (Jupa, Romania), before they headed towards Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.[2] Land in Dacia was assigned to 12,000 tribespeople who had been driven from their territories outside the empire and who seemed to pose a threat if they were left to roam.[7]

The Free Dacians of Crişana, sandwiched between the attacking Germans and resisting Romans, sided with the latter because the unwanted invaders endangered their nation.[2] This was the first sign of successful Dacian-Roman cooperation against a mutual enemy and a step toward a peaceful co-existence.[2] Marcus Aurelius reinforced the province with the legion V Macedonica;[15] a road was also built between Napoca and Porolissum to facilitate the rapid movement of troops to the troubled northern part of Transylvania.[2] However, the Roman troops deployed there to push back the Iazyges encountered unexpectedly strong resistance.[2] During the winter of 172-173, a coalition of Iazyges and Free Dacians attacked Roman strongholds on the Danube and the Tisa.[2] The Romans’ campaign was unsuccessful in evicting the barbarians, and the Roman commander, Claudius Fronto was killed in a battle[15]

Marcus Aurelius responded by leading a punitive expedition, and he obtained a much-needed victory that led to his being named Dacicus Maximus.[2] Determined to spare his troops from endless fights, the emperor permitted the Iazyges to leave the plains of Pannonia at any time to visit their Roxolani cousins, and he also allowed the Roxolani to visit Pannonia.[2]

By the end of the long war, Rome had rebuilt its network of alliances along the border of the empire.[8] However, Germans had begun to settle on the northern approaches to Dacia, and fighting would flare up again.[8] Around 180, Commodus, the son of Marcus Aurelius, waged war in this region, principally against the Buri.[8]

Commodus granted peace to the Buri when they sent envoys. Previously he had declined to do so, in spite of their frequent requests, because they were strong, and because it was not peace that they wanted, but the securing of a respite to enable them to make further preparations; but now that they were exhausted he made peace with them, receiving hostages and getting back many captives from the Buri themselves as well as 15,000 from the others, and he compelled the others to take an oath that they would never dwell in nor use for pasturage a 5-mile strip of their territory next to Dacia. The same Sabinianus also, when twelve thousand of the neighboring Dacians had been driven out of their own country and were on the point of aiding the others, dissuaded them from their purpose, promising them that some land in our Dacia should be given them.—Cassius Dio: Roman History – Epitome of Book LXXIII[16]

During Commodus’s reign, unrest and disturbances were rife among the people of Dacia; it is briefly noted in the emperor's biography that a local revolt broke out in Dacia around 185.[8] There is also mention in his biography of a defeat of the Free Dacians.[8] He created a no-man’s-land 5 miles (c. 8 kilometers) deep north of the military camp at today’s Gilău to discourage the barbarians.[1]

The Moors and the Dacians were conquered during his reign, and peace was established in the Pannonias, but all by his legates, since such was the manner of his life. The provincials in Britain, Dacia, and Germany attempted to cast off his yoke, but all these attempts were put down by his generals.—Historia Augusta – The Life of Commodus[17]

Revival under the Severans (193-235)

Dacia remained free of foreign attacks during Septimius Severus’ reign; damage caused by the long war to military camps was repaired.[8] He pushed Dacia’s eastern frontier approximately 10 to 14 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) east of the river Olt (Limes Transalutanus), constructing a series of 14 camps, over a distance of c. 225 kilometers (140 miles), beginning at Flăminda on the Danube and stretching northward to Cumidava (Breţcu, Romania).[1] He almost doubled the number of Roman cities in Dacia.[2] In his reign, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Apulum acquired the ius Italicum.[5]

Septimius Severus was the first emperor to legalize marriage between soldiers and local women; he permitted the troops to live off base, in the canabae, and to cultivate plots of land nearby.[1] If the husband was a Roman citizen, so were his children; if he was not, he and his children gained citizenship on his discharge.[1]

Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants within the imperial borders was given by Caracalla who wanted to expand the internal tax base and gain increased popularity.[2] He continued to fortify the Limes Transalutanus in the north.[2]

The Carpi invaded Dacia once more and were promptly annihilated by Caracalla’s legions.[2] The emperor himself led the military expedition from Porolissum.[2] By forcing the barbarians eastward, the legionaries also extended the border of Dacia toward Braşov.[2] One year after Emperor Caracalla died, the Free Dacians raided Dacia and demanded that their warriors (those taken prisoners during an earlier rebellion against Roman occupation) be released in exchange for peace.[2]

And the Dacians, after ravaging portions of Dacia and showing an eagerness for further war, now desisted, when they got back the hostages that Caracallus, under the name of an alliance, had taken from them.—Cassius Dio: Roman History – Epitome of Book LXXIX[16]

Few epigraphs remain in Dacia dating from the time of the last Severus emperor, Alexander Severus (222–235).[8] Under his reign, the Council of Three Dacias met at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, and the gates, towers, and praetorium of Ad Mediam (Mehadia, Romania) camp was restored.[1]

Life in Roman Dacia

Native Dacians

There is less evidence regarding the existence in Roman Dacia of indigenous Dacians than in the case of Illyrians and Thracians, or of Celts and Germans in other provinces.[18] The presence of indigenous Dacians is poorly documented in the territories of the Roman towns.[18]

It is the desperation and stubbornness of Dacian resistance, illustrated in the siege and conquest of Sermizegetusa Regia and the final suicide of the king Decebalus, that is used by modern commentators to explain the unbelievable treatment applied to the natives after the conquest, as described by the literary sources (Eutropius, Cassius Dio and Julian the Apostate)[9], including severe depopulation and deliberate ethnic cleansing.[5] According to concurring interpretations, the last scene on Trajan’s Column may show either emigrating Dacians whose departure also contributed to the depopulation of Dacia,[9] or Dacians returning to their settlements and submitting to the new authorities.[6]

Archaeological evidence from hillforts and other types of settlement, especially from the Oraştie Mountains, shows deliberate destruction: continuity of occupation is likely to have been the exception rather than the rule.[5] Excavated villages of traditional architectural type (e.g. Obreja, Noşlac) show that they started at the same time (at the beginning of the 2nd century AD) as those of the Roman type.[5]

Very few settlements in Dacia have been proved to be continuously occupied from the pre- to the post-conquest period; the most famous examples are the settlements at Cetea and Cicau.[5] The continuous occupation was documented largely by pottery; other aspects of continuity have been detected in architecture, such as the persistence of traditional forms of sunken houses and storage pits in several locations including where continuity of site occupation was not necessarily applicable (e.g. Obreja, which is a post-conquest foundation).[5] Some 46 sites have been documented on the same location in both La Tène and Roman periods, and future research could prove their continuous occupation more explicitly.[5]

Archaeology shows a continuing Dacian presence, with the process of Romanization clearly in evidence.[6]

- The traditional Dacian style of pottery is found in the settlements alongside vessels of Roman manufacture but with local decorative elements.[6] On the other hand, only a few earlier Dacian styles were carried over into the pottery of the Roman era: the pots and the so-called Dacian cup (a low, thick-walled mug that broadens towards the mouth and has one or, more rarely, two handles); they were generally hand-crafted, and examples of wheel pottery are rare.[8]

- Dwellings were constructed largely by old Dacian methods, and the types of tools and ornaments used before the Roman conquest persisted.[6]

- Research on cemeteries clearly shows that the continuing population was far too great to have been wiped out or driven away.[6] But it is arguable that at least some of the graves belong not to aboriginal Dacians, but to Carpi or Free Dacians who moved into Dacia shortly before 200 (the silver jewellery, bearing a granular decoration, that has been found in some cemeteries can be most plausibly attributed to Carpi).[8]

One of the weightiest counter-arguments against the survival of Dacian natives is the lack of civitates peregrinae which were native communities organized by the Romans.[9] On the other hand, before the Roman conquest, Dacia had been an unified state, under the rule of one king and not a regional tribal structure which could have been easily converted to the Roman civitas system.[5] Apparently, no native Dacians partook of the creation of epigraphs, which was an intrinsic part of Roman culture and daily life.[8]

Dacian men were conscripted into auxiliary units and sent to Britannia or to the east.[8] Cohorts Primae Dacorum such as II Ulpia Dacorum and Aurelia Dacorum, were stationed in Pannonia.[2] Others served in Britannia: Alea Dacorum could be found at Deva (Chesters, UK) and Camboglanna, while cohort I Aelia Dacorum miliaria was based at Birdoswald.[2] The largest number of relics we have came from this cohors; one inscription portrays the sica, a unique Dacian weapon.[9] The cohort I Ulpia Dacorum marched to Syria, and Vexillation Dacorum Parthica took part in Septimius Severus’s Parthus campaign.[2] Some of the soldiers serving outside Dacia indicated their natione Dacus; they could have been originally Dacians, but also completely Romanized, or simply coming from the province of Dacia which did not made them Dacian in origin.[18]

Colonists

Hoping to populate the cities, tilling the earth and extracting the ore, the Roman authorities unfolded in Dacia a massive and organized colonization, with people brought over “from all over the Roman world”.[4]

The colonizing population was clearly heterogeneous: of the some 3,000 names preserved in inscriptions found to date, 74% (c. 2,200) are Latin,[6] 14% (c. 420) are Greek, 4% (c. 120) are Illyrian, 2,3% (c. 70) are Celtic, 2% (c. 60) are Thraco-Dacian, and another 2% (c. 60) are Semites from Syria.[8] But whatever their origins, the colonists represented imperial culture and civilization and brought with them that most powerful Romanizing instrument, the Latin language.[6]

The first group to be settled, at Sarmizegethusa, consisted of veterans of the legions, who were Roman citizens.[8] On the basis of the geographical incidence of personal names, it can be concluded that a significant proportion of the settlers came from western Pannonia and Noricum, even though such origin is rarely indicated in epigraphs.[8]

Expert miners (the Pirusti tribesmen)[2] were imported from Dalmatia.[1] These Illyrian miners lived in closed communities (Vicus Pirustarum), with their own tribal leaders (princeps).[8]

Roman army in Dacia

The occupation army of Dacia – estimated, at its height, at over 50,000 men –[1] has been the subject of much debate.[5]

In 102 when his first war ended in Dacia, Trajan left one legion at Sarmizegetusa Regia.[5] After the wars ended there were two legions in the area, the Legio XIII Gemina based at Apulum and the Legio IV Flavia Felix at Berzobis.[5] A third possible legion involved was the Legio I Adiutrix, but so far neither its precise location nor chronology of occupation in Dacia have been confirmed, or, indeed, whether it was present in full or just through vexillationes.[5]

The Legio IV Flavia Felix was moved at a later date by Hadrian from Berzobis to Singidunum in Upper Moesia on the Danube, so the presence of only one legion seems to have looked sufficient for the rest of the first half of the 2nd century.[5] This proved to be wrong during the events of the Marcomanic Wars, when the Legio V Macedonica had to be transferred permanently from Troesmis (Igliţa, Romania)[1] in Lower Moesia to Potaissa in Dacia.[5]

The numerous auxiliary units attested in the Dacian provinces during the period of Roman occupation, mainly through epigraphic evidence, contributed to building the image of Roman Dacia as a heavily militarized province.[5] Various military diplomas mention no less than 58 units, most of them coming into Dacia from the neighboring provinces (the Moesias and the Pannonias), covering a complete range of troops: alae and cohortes militariae and quingenariae as well as numeri, along with significant variation in their ethnic origin.[5] However, this does not mean that all these troops were stationed in Dacia at the same time and throughout the entire period of Roman occupation.[5]

Settlements

The settlement pattern of Roman Dacia is traditionally interpreted as consisting of urban-satus settlements (coloniae and municipia) and of rural settlements as villas and villages (vici).[5] The two major towns of Dacia (Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Apulum) clearly demonstrate a level of Roman architectural and socio-economic development rivaling that seen anywhere in the western empire.[5]

Romanization is essentially a culture of cities; and Roman Dacia had 11 (or 12)[6], all developed from Trajanic camps.[1] There were two types of towns: the most important were the so-called coloniae, inhabited exclusively by Roman citizens; municipia were localities of secondary importance, enjoying, nevertheless, administrative and juridical autonomy.[4]

- Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, the first colonia of Dacia and the only colonia deducta, was founded by Trajan.[5] Its status at the top of the settlement pattern of the province ensured by its charter (further reinforced by the later acquisition of ius Italicum) is reinforced by its significant administrative role.[5]

- Apulum started its existence as a legionary base under Trajan.[5] The canabae legionis emerged immediately in its vicinity; and already in the Trajanic period a civilian settlement also emerged some 2 leuga (c. 4,4 kilometers) away from the fort by the Mureş River.[5] This settlement developed rapidly from a vicus of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa into a municipium (under Marcus Aurelius), then a colonia (under Commodus). Apulum was the capital of Upper Dacia/Dacia Apulensis, and the military headquarters of the whole tripartite province.[1] When Septimius Severus finally gave municipal status to a part of the canabae (which subsequently may have also reached colonial rank), the town was a clear competitor to Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.[5]

- The most important Roman town of south Dacia was Drobeta; it grew up around the site of a Trajanic stone camp, built to hold 500 men whose job was to guard the head of Apollodorus’s bridge.[1] The civilian town that grew up around the camp was made a municipium, with the rights of an Italian town, by Hadrian.[1] Between 193 and 198, Septimius Severus raised the municipium to the rank of colonia.[1]

- Romula was the possible capital of Lower Dacia/Dacia Malvensis.[1] It became municipium perhaps under Hadrian’s reign, and a colonia under Septimius Severus.[1]

- Napoca, which was probably the location of command of Dacia Porolissensis,[5] was made a municipium by Hadrian; and Commodus made it colonia.[1]

- During the Marcomannic Wars, the Legio V Macedonica was brought to Potaissa[5] where a canabae had grew up at the camp gates.[1] Under Septimius Severus Potaissa became a municipium, under Caracalla a colonia.[1]

- Porolissum is unique in having two camps, adjacent to a regular walled frontier, the only such stretch so far discovered in Dacia.[1] Porolissum was made a municipium in the reign of Septimius Severus; it never achieved the status of colonia.[1]

- Dierna (Orşova, Romania), Tibiscum (Jupa, Romania) and Ampelum (Zlatna, Romania) were also important Roman towns,[1] although the legal status of Ampelum (the largest settlement in the mining district) is uncertain.[8] Dierna was a customs station, and by Septimius Severus’s reign it was a municipium.[1]

- In Sucidava (now Celei-Tismana), Trajan built an earthwork camp; and after the war, a town grew up on the site of the camp.[1] Sucidava never became a municipium or a colonia: its status was always that of a pagus or a vicus, a simple country town.[1]

It is often difficult to define the boundary between the ‘Romanised’ villages and most of the sites that fall under the category of ‘small towns’.[5] Therefore, identifying such sites has tended to focus on those which operated beyond a purely subsistence economic level and, at least in part, were involved in trade and industry.[5] The itinerary depicted by the Tabula Peutingeriana mentions the following settlements along the main route within the province: Aquae (Călan, Romania), Petris, Germisara (Cigmău, Romania), Blandiana and Brucla.[5] In cases of Aquae and Germisara their functional complexity is evident: both were based on natural springs still in use today.[5] The identifications of Petris, Blandiana and Brucla have not yet been confirmed epigraphically.[5] If Petris was, indeed, located at Uroi (Romania), it would have been primarily an industrial centre, which would have also been an important site for trade and the communication network.[5]

In Dacia, there are a lot of settlements supposedly connected with military sites (military vici).[5] Unfortunately, in many cases this is merely an assumption where a fort is known, or where a fort is assumed.[5] However, few of these sites have been examined in any detail; in the mid-Mureş valley, civilian settlements were identified outside the auxiliary forts at Micia (Veţel, Romania), Cigmău, Războieni and Orăştioara de Sus.[5] The most interesting discovery at Micia is a small amphitheatre.[1]

During the period of Roman occupation, the settlement pattern of the Mureş valley shows a significant shift towards nucleation.[5] In central Dacia, there are approximately 10 villages (aggregated settlements) of most likely agricultural function, and a further 18 sites may also fit into this category.[5] The layout of all these examples follows two main types.[5] On one hand, there are the examples built in a traditional manner (e.g., Obreja, Vinţu de Jos, Radeşti), many still with largely sunken houses and in a few examples showing evolution towards surface timber constructions; on the other hand, there are those built in the Roman fashion.[5]

The total number of villas within central Dacia is uncertain, much like elsewhere in the province.[5] Less than 30 appear on the published heritage lists throughout the province, but this is clearly an underestimate.[5]

Economy

Under the peace kept by the army of occupation, at least until the middle of the 3rd century, Dacia prospered, and enjoyed the blessings of Romanization: Rome raised this latest of her provinces, as she had the others, from an underdeveloped country to an advanced level of material civilization.[1] From the year 106 to the middle of the 3rd century, there were more coins circulating in Dacia than in the neighboring provinces.[18]

The country’s resources, skillfully exploited, brought Rome considerable wealth.[6] Dacia became one of the principal producers of grain, especially wheat, in the empire.[6] To facilitate commerce Roman bronze coins were minted in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa[6] between 246 and 256 (previously Dacia seems to have been supplied with coins from central coin-issuing mints).[18] The extensive network of Roman roads contributed to the growth of the economy.[6]

The gold mines had been one of the major attractions of Dacia for the Romans from the beginning;[1] and the gold mines of the Bihor Mountains, operated by Illyrians brought in from Dalmatia, were an important resource for the empire's treasure chests.[6] At Alburnus Maior the gold mines flourished between 131 and 167, but the mines were still worked though with reduced production; perhaps the veins were giving out.[1] The last evidence of Roman exploitation of the gold mines dates from 215.[1]

The lead, copper, silver, iron, and salt mines, which, like the gold mines, had existed in the time of the Dacian kings, were systematically worked as well.[6] The country was also rich in building-stone: marble, limestone, andesite, sandstone, and schist.[1]

Towns represented important manufacturing centers.[18] Weapons workshops were attested in Apulum, a brooch workshop in Napoca, bronze casting workshops were found in Dierna, Romula, and Porolissum.[18] Glass manufactures were discovered in Tibiscum and Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa.[18] Dacia’s rural settlements often specialized in specific craftsmanship activities, especially pottery (e.g., at Micăsasa 26 kilns and hundreds of moulds fragments for local terra sigillata were unearthed).[18]

Religion

To illustrate religious beliefs, Dacian inscriptions and sculpture have more variety to offer than those of any other Roman province.[1] It is not only the gods of the official state religion that are represented; there is also a whole gamut of divinities from the Greek east and the “barbarian” west.[1]

- Of the divinities worshiped, 43,5% have Latin names.[6] All the gods of the Roman pantheon are represented in Dacia;[1] the new gods were Jupiter, Juno, Minerva, Venus, Apollo, Liber, Libera and others.[4] Dacia was one of the locations where the Roman god Silvanus was of prime importance (on the inscriptions he is second only to Jupiter similarly to the city of Rome and Pannonia).[19] In Dacia, Silvanus appears to have had strong connections with the highly Romanized version of the cult in Pannonia: his most frequent titles in Dacia are domesticus and silvester, which were popular also in Pannonia.[19]

- 20% of the inscriptions found in Dacia refer to Oriental cults; for example, from Asia Minor came Cybele and her votary Attis; over 274 dedications to Mithras (who was most popular among soldiers) are known in Dacia[1]

- The cult of the ‘Thracian Rider’ came from Thrace and Moesia.[1]

- The most important Celtic cult attested in Dacia is that of the horse-goddess Epona.[1]

- Among Germanic goddesses, the fertility deities called Matronae deserve mention.[1]

Apparently no Dacian good creeps into the Roman pantheon;[5] there are no references to Dacian cults or a Dacian deity on religious memorials, nor any indication that the Dacians might have worshipped a local deity who, due to interpretatio Romana, bore a Roman name.[8] The main reason for this may be that the Dacians did not conceive their gods anthropomorphically;[1] the Thraco-Dacian religion was characterized by aniconism to such an extent as Judaism and Islam.[20] No statues were found in the columned sanctuaries of the Dacian citadels dated in the reigns of Burebista and Decebalus.[1] The main Dacian sacred site was destroyed during the wars and the place was doomed; but other places of religious significance (Germisara) where the pre-Roman use of the site is combined in the post-conquest period with particular nuances in cult and worship show that some elements of the Dacian supernatural did survive, despite the Roman names applied to local divinities.[5]

It is clear that in general the funerary practices in Roman times contrast significantly with those in the period before the Roman conquest when very few such contexts have been documented.[5] Most of the recovered funerary art comes from major towns; it demonstrates that, although stelae were the most common type of funerary monument, more elaborate monuments were also present, such as mausoleum, tumulus, aedicule, funerary enclosure and segmented pyramidal-shaped or altar-shaped monuments, most of them with architectural decoration (e.g., funerary medallions, copings, columns, funerary lions).[5] Few cemeteries have been excavated in the rural areas, where work has focused mostly on those identified as of Dacian type. Some funerary sites are, or assumed to be, related to villa settlements (certain – Cincis; assumed – Deva, Ghirbom, Sălaşu de Sus, Orăştioara de Jos, Hăpria).[5]

There is no evidence of Christianity in Dacia until after the Roman withdrawal.[1]

Last decades of Dacia Traiana (235-271/275)

The decade of the 220s was the last peaceful period in Dacia's history.[8] The finding of a huge hoard of 8,000 coins at Romula, ranging in date from Commodus to Elagabalus (217-222) shows that insecurity antedated the mid-3rd century.[1]

The accession of Maximinus Thrax (235-238) marked the start of a 50-year period of disorder in the Roman Empire during which the militarization of the government inaugurated by Septimius Severus continued apace and the debasement of the currency brought the empire to bankruptcy.[15] As the middle of the 3rd century approached, a mighty swarm of Germanic tribes, migratory Goths, appeared on the horizon of the Danube.[2] In or around 235, the Goths and Carpi occupied Histria and sacked the Danube Delta’s prosperous commercial centers, which had also served as important economic links for Dacia.[8] The evidence of excavation is that the Limes Transalutanus did not last much beyond the reign of Gordian III (238-244): it was probably abandoned in the face of the invasion of the Carpi.[1]

At this point of history, Rome’s only real option was to pay off the Dacian Carpi, Goths, and other barbarians in exchange for peace in Moesia.[2] When Philip the Arab (244-249) refused to pay the annual tribute in 245, the next year the Carpi entered Dacia and destroyed the city of Romula;[2] and the Carpi probably also burned the camp at Răcari between 243 and 247.[1] The governor of Lower Moesia was not able to check the invaders; accordingly the emperor left Rome to take charge of the situation.[15] The mother of a later Emperor, Galerius, fled during this period from Dacia Malvensis to Lower Moesia.[9]

But the other Maximian /Galerius/, chosen by Diocletian for his son-in-law, was worse, not only than those two princes whom our own times have experienced, but worse than all the bad princes of former days. In this wild beast there dwelt a native barbarity and a savageness foreign to Roman blood; and no wonder, for his mother was born beyond the Danube, and it was an inroad of the Carpi that obliged her to cross over and take refuge in New Dacia.—Lactantius: Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died – Chapter IX[21]

At the end of 247 the Carpi were decisively beaten in open battle and sued for peace;[15] Philip the Arab took the title of Carpicus Maximus.[2] In Sucidava, probably after a raid (245-247) by the barbarians, the townsfolk hastily threw up a trapezoidal stone wall and ditch; the building of the third phase of Romula’s town wall, in 248, was also a defensive measure against the invading Carpi.[1] An epigraph in Apulum hails Emperor Decius (249-251) as restitutor Daciarum (the 'restorer of Dacia').[8] On July 1, 251 Decius was slaughtered by the Goths after his defeat in the Battle of Abrittus (Razgard, Bulgaria).[15] The Goths now dominated the territories of the lower Danube and the western shore of the Black Sea; their influence in Free Dacia and their massive presence around Roman Dacia was overwhelming.[2]

Decius appeared in the world, an accursed wild beast, to afflict the Church, – and who but a bad man would persecute religion? It seems as if he had been raised to sovereign eminence, at once to rage against God, and at once to fall; for, having undertaken an expedition against the Carpi, who had then possessed themselves of Dacia and Moesia, he was suddenly surrounded by the barbarians, and slain, together with great part of his army; nor could he be honored with the rites of sepulture, but, stripped and naked, he lay to be devoured by wild beasts and birds, – a fit end for the enemy of God.—Lactantius: Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died – Chapter IV[22]

Emperor Gallienus’s many victorious fights against the Carpi and other Free Dacians brought him the title of Dacicus Maximus.[2] However, literary sources from antiquity (Eutropius, Aurelius Victor and Festus) inform us that Dacia was lost under his reign.[9] He moved many cohorts of legions V Macedonica and XIII Gemina from Dacia to Pannonia.[2] The latest coins at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and Porolissum bear his effigy.[1] The erection of inscribed monuments in Dacia was essentially halted in 260, during Gallienus’s reign.[8]

Even the territories across the Danube, which Trajan had secured, were lost.—Aurelius Victor: De Caesaribus[23]

In an attempt to boost the confidence of the Roman colonists, Aurelian minted coins which bear the inscription DACIA FELIX (‘Fruitful or Happy Dacia’) around 270.[2] But finally, he was forced to accept the vulnerability of Dacia Traiana to repeated Gothic invasions.[15] Reluctantly he decided to abandon the province and save the ruinous cost of garrisoning it.[15] Dacia was officially abandoned in 271;[1] other view is that Aurelian evacuated his troops and civilian administration only by 274[2] or 275.[4]

The province of Dacia, which Trajan had formed beyond the Danube, he gave up, despairing, after all Illyricum and Moesia had been depopulated, of being able to retain it. The Roman citizens, removed from the town and lands of Dacia, he settled in the interior of Moesia, calling that Dacia which now divides the two Moesiae, and which is on the right hand of the Danube as it runs to the sea, whereas Dacia was previously on the left.—Eutropius: Abridgement of Roman History[24]

Moving the Romanized population to the river’s southern shore went a long way towards repopulating the provinces of Moesia, Pannonia and Thracia that had been ravaged by barbarian invasions and the recurrent plague.[15] So the emperor created a new province of Dacia,[15] “Dacia Aureliana” with its capital at Serdica in Lower Moesia.[2]

After the Roman withdrawal

Semi-official Roman historians noted that the population of Dacia Traiana was moved south when Aurelian abandoned the province.[3] Once the Romans withdrew from Dacia Traiana, the inhabitants of the Carpathian-Danubian region north of the Danube were no longer of interest to historians: with respect to the north, history, for the next 600 years, records for the most part only the struggle of the Roman Empire against the barbarian invasions.[3] Because of this lengthy period of historical stealth, two theories about the origins of the Romanians developed that were subsequently exploited for political reasons.[3]

- One theory holds, that the Romanization of Dacia and the birth of a Daco-Roman people can be considered the first stage in the long process of the formation of the Romanian people, but this stage did not end in 275.[6] Excavation of settlements and cemeteries vouches for the continuance of the native population.[1] For example, a large necropolis in Potaissa’s cemetery shows by pottery dated after 271 that the natives stayed when the Romans left; in Napoca, coins of Tacitus (275-276), and of Crispus (son of Emperor Constantine the Great, appointed Caesar in 317) also show that it continued thereafter; in Porolissum Roman coinage began to circulate again under Valentinian I (364-375); in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa the native stayed, eking out a miserable existence, as the pathetic attempt to fortify the amphitheater shows[1] Therefore, the formation of the Romanian people continued until the early 6th century, as long as the empire, still in power along the Danube and in Dobrudja, continued to influence the territory north of the river.[6] The continual circulation of people and goods across the river and back certainly facilitated this.[6]

- The opposing theory argues that the relocation of Dacia’s reduced population coincided with the need to repopulate the Balkans.[8] Therefore, it is just possible that some of the inhabitants stayed behind, and their numbers could not have been significant.[8] The extent of toponymic change also confirms this wholesale withdrawal: without exception, the names of onetime Roman towns, settlements, and fortresses fell into oblivion.[8] Two hundred years' worth of archaeological research in Transylvania has failed to produce conclusive evidence that a significant part of Dacia’s ‘Roman’ population survived Roman evacuation;[8] for example, traffic in Roman coins in the former province after 271 show similarities to modern Slovakia and the steppe in what is today Ukraine.[9] On the other hand, linguistic data and place names[8] attest to the beginnings of the Romanian language in Lower Moesia,[9] or other provinces south of the Danube of the Roman Empire.[8]

As the Emperor Galerius is said to have complained, the Danube was perhaps the most difficult frontier of the Roman Empire of all: apart from its great length, much of it was unsuited to the kind of warfare in which the Romans excelled.[25] The Romans kept enclaves on the north bank of the Danube even after the official abandonment of Dacia Traiana province.[1] For example, Aurelian retained the bridgehead camp at Drobeta; in Desa an inscription shows that there was a detachment of the Legio XIII Gemina on station between 275 and 305; coins show that after the end of Roman Dacia Dierna lived on till the reign of Arcadius (383-408).[1] During 294-5, Diocletian, who had earlier established advance bases across the Danube along the 200-mile (c. 320-kilometer) sector of river flowing due south from Aquincum (Budapest, Hungary), continued the inspection and reorganization of the defences, traveling from Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) to Ratiaria, then east to Durostorum (Silistra, Bulgaria).[25] His new installations served to protect the main crossing points, to act as lookout stations and bases for river patrols, and to allow the transfer of strong forces across the river Danube.[25]

Under Constantine the Great, Sucidava also got a new lease on life: in 328, he built a bridge across the Danube here.[1] In the spring of 336, the emperor led his armies above the arc of the lower Danube, defeated many of the Gothic tribes, and reestablished a Roman province in the region which allowed him to add the title Dacicus Maximus to his victory titulature as the 30th anniversary of his rule in the Roman Empire was nearing its climax in the summer of 336.[26] The bridge built at Sucidava lasted less than 40 years: the Emperor Valens (364-378) was unable to use it for his expedition north of the Danube against the Goths in 367.[1] But the citadel continued in use until Attila the Hun destroyed it in 447.[1]

On the territories north of the Danube, earlier arrivals (the Quadi, Carpi, Bastarnae and Sarmatians) were under growing pressure from the Vandals in the north, and the Goths and the Gepids in the north east and east.[25] Outnumbered and penned into ever smaller areas by the new migrants, they invariably burst into Roman territory whenever its defenses were weak, mixing threat with supplication, respectfully seeking living space in the Empire, then warning of desperate invasion if it was not granted.[25] Eventually, the surviving Carpi were settled to the west of their original homeland in the newly created Pannonian province of Valeria, while the Bastarnae were settled at Thrace.[25] But the Carpi were far from being annihilated or incorporated within the Roman Empire: those who remained outside the Empire were evidently styled Carpodacae (“Carps from Dacia”).[27] In 334, the majority of the Sarmatians asked Constantine to allow them to settle peacefully south of the Danube.[28]

Links

See also

- Roman provinces

- History of Romania

- Romanization

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 1.48 1.49 1.50 1.51 1.52 1.53 1.54 1.55 1.56 1.57 1.58 1.59 1.60 1.61 1.62 1.63 1.64 1.65 MacKendrick, Paul. The Dacian Stones Speak.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 2.37 2.38 2.39 2.40 2.41 2.42 2.43 2.44 2.45 2.46 2.47 Grumeza, Ion. Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Klepper, Nicolae. Romania: An Illustrated History.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Pop, Ioan Aurel. Romanians and Romania: A Brief History.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 5.41 5.42 5.43 5.44 5.45 5.46 5.47 5.48 5.49 5.50 5.51 5.52 5.53 5.54 5.55 5.56 5.57 5.58 5.59 5.60 5.61 5.62 5.63 5.64 5.65 5.66 5.67 5.68 5.69 5.70 5.71 Oltean, Iona A.. Dacia: Landscape, Colonisation, Romanisation.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 Georgescu, Vlad. The Romanians - A History.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Grant, Michael. The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 8.28 8.29 8.30 8.31 8.32 8.33 8.34 8.35 8.36 Köpeczi, Béla; Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Szász, Zoltán; Barta, Gábor. History of Transylvania - From the Beginnings to 1606.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Vékony, Gábor. Dacians–Romans–Romanians.

- ↑ Festus (2001-01-31). "Breviarium of the Accomplishments of the Roman People". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families. http://www.roman-emperors.org/. http://www.roman-emperors.org/festus.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Burns, Thomas S.. Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.-A.D. 400.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Bennett, Julian. Trajan: Optimus Princeps.

- ↑ Pliny, The Younger. Letters.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 Birley, Anthony R.. Hadrian: The Restless Emperor.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 Kean, Oliver. The Complete Chronicle of the Emperors of Rome.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Cassius Dio (2006-10-09). "Roman History". LacusCurtius: Into the Roman World. www.penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/home.html. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/home.html. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ unknown (2006-10-09). "Historia Augusta". LacusCurtius: Into the Roman World. www.penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/home.html. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Historia_Augusta/Commodus*.html#ref103. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 Opreanu, Coriolan Horaţiu. The North Danube Regions from the Roman Province of Dacia to the Emergence of the Romanian Language (2nd-8th Centuries A. D.).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dorcey, Peter F.. The cult of Silvanus: A Study in Roman Folk Religion.

- ↑ Paliga, Sorin. La divinité suprême des Thraco-Daces.

- ↑ Lactantius (2005-06-09). "Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died". People. www.earlychurch.org.uk – An Internet Resource for Studying the Early Church. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07.iii.v.ix.html. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ Lactantius (2005-06-09). "Of the Manner in which the Persecutors Died". People. www.earlychurch.org.uk – An Internet Resource for Studying the Early Church. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07.iii.v.iv.html. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Victor, Aurelius. De Caesaribus.

- ↑ Eutropius (1853). "Abridgement of Roman History". Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum. Henry G.. Bone. http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/eutropius/trans9.html#12. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Stephen, Williams. Diocletian and the Roman Recovery.

- ↑ Odahl, Charles Matson. Constantine and the Christian Empire.

- ↑ Nixon, C. E. V.; Saylor Rodgers, Barbara. In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panergyc Latini.

- ↑ Kousoulas, D. G.. The Life and Times of Constantine the Great.

Sources

- Bennett, Julian: Trajan: Optimus Princeps; Routledge, 1997, London and New York; ISBN 978-0-415-16524-5

- Birley, Anthony R.: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor; Routledge, 2000, London and New York; ISBN 0-415-22812-3

- Burns, Thomas S.: Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.-A.D. 400; The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, Baltimore and London; ISBN 0-8018-7306-1

- Dorcey, Peter F.: The cult of Silvanus: A Study in Roman Folk Religion; Brill Academic Publishers, 1992; ISBN 90-04-09601-9

- Georgescu, Vlad: The Romanians: A History; Ohio State University Press, 1991, Columbus; ISBN 0-8142-0511-9

- Grant, Michael: The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition; Routledge, 1996, New York; ISBN 0-415-13814-0

- Grumeza, Ion: Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe; Hamilton Books, 2009, Lanham and Plymouth; ISBN 978-0-7618-4465-5

- Klepper, Nicolae: Romania: An Illustrated History; Hippocrene Books, 2005, New York; ISBN 0-7818-0935-5

- Kean, Roger Michael – Frey, Oliver: The Complete Chronicle of the Emperors of Rome; Thalamus Publishing, 2005, Ludlow; ISBN 1-902886-05-4

- Kousoulas, D. G.: The Life and Times of Constantine the Great; Provost Books, 2003, Bethesda; ISBN 1-887750-61-4

- Köpeczi, Béla (General Editor) – Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Szász, Zoltán (Editors) – Barta, Gábor (Assistant Editor): History of Transylvania; Akadémiai Kiadó, 1994, Budapest; ISBN 963-05-6703-2

- MacKendrick, Paul: The Dacian Stones Speak; The University of North Carolina Press, 1975, Chapel Hill; ISBN 0-8078-1226-9

- Nixon, C. E. V. – Saylor Rodgers, Barbara: In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panergyc Latini; University of California Press, 1995; ISBN 978-0-520-08326-4

- Odahl, Charles Matson: Constantine and the Christian Empire; Routledge, 2004, New York & Oxon; ISBN 0-415-17486-6

- Oltean, Ioana A.: Dacia: Landscape, Colonisation, Romanisation; Routledge, 2007, London and New York; ISBN 978-0-415-41252-0

- Opreanu, Coriolan Horaţiu: The North Danube Regions from the Roman Province of Dacia to the Emergence of the Romanian Language (2nd-8th Centuries A. D.); in: Ioan-Aurel Pop – Ioan Bolovan (Editors): History of Romania: Compendium; Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies), 2006, Cluj-Napoca; ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4

- Paliga, Sorin: La divinité suprême des Thraco-Daces; in: Ballesteros Pastor, Luis (Editor): Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, Vol. 2. ; l’Université de Besançon (in collaboration with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), 1994, Paris; ISBN 2-251-60545-2

- Pliny the Younger (Author) – Radice, Betty (Translator, Introduction): The Letters of the Younger Pliny; Penguin Books, 1969, London, New York; ISBN 978-0-14-044127-7

- Pop, Ioan Aurel: Romanians and Romania: A Brief History; Boulder (distributed by Columbia University Press), 1999, New York; ISBN 0-88033-440-1

- Williams, Stephen: Diocletian and the Roman Recovery; Routledge, 2000, London and New York; ISBN 0-415-91827-8

- Vékony, Gábor: Dacians, Romans, Romanians; Matthias Corvinus Publishing, 2000, Toronto-Buffalo; ISBN 1-882785-13-4

- Victor, Aurelius (Author) – Bird, H. W. (Translator and Commentator): De Caesaribus; Liverpool University Press, 1994, Liverpool; ISBN 0 85323 218 0

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||